It was a crisp October evening of a football game in Texas, 2007. I stood under the bleachers with the other girls of the Arbor Creek Middle School dance team and eagerly anticipated our halftime show entrance. Then, a slow creeping anguish took over. It was barely evening and the autumnal sky had darkened. I knew that in a few weeks, the time would change and this darkness would come even earlier in the day. I didn’t want the days to be taken away. Standing there with my hairsprayed top bun and sparkling pom poms, I was startled by the onset of my bizarre sadness.

This would be the first experience of many in my life where I feel like happiness fades away for no reason. Whenever I get depressed now, I travel back to the purple air of the football field, the bright stadium lights, the turf. As I’ve grown older, I’ve come to understand the depression better. Now, I don’t try to get rid of it but see it as part of my internal landscape.

Last fall, I felt like I was there again. But I was in Chicago, my home of eight years. It was the end of daylight savings and that weird feeling returned, like someone was trying to steal my days. To enliven me, my husband Andy took me to the nursery and bought me a tree. I put the tree indoors and stared at it, but still felt like the days were being stolen.

“I don’t know if I like living here,” I confessed to myself, watching the days get shorter, watching the shadow of the tree move quicker across the floor by the minute. It was not an easy feeling. Contentment in Chicago can be hard for me, especially during months with so little light.

I decided that I needed to find something to do during winter. I discovered that the inherent problem with the season, for me, is that it’s the time to be cozy, and I don’t really like being cozy. I like going out in the sun, I don’t like the obligatory hugs of holidays, and I don’t like wearing a lot of clothes. So after thinking about this and staring at my tree for a long while, I concluded that I wanted to spend winter learning more about gardening.

Once the air dipped to 30 degrees, I threw myself in full force.

Every night, as soon as my two-year-old son Augie went to bed, I curled up by the lamp and read everything I could about agriculture, horticulture, and permaculture. First, I started with houseplants. I learned about the plants I already owned, aroids, which are plants that thrive in swamps and on the forest floor, but do okay in most homes. They can survive all over the world except Antarctica and can handle a significant amount of neglect. Aroids are so hard wearing that they can actually generate heat. For this reason, they are some of the first plants to appear in spring—to melt the ice. Many people, like me, use aroids as a gateway into gardening because they demand so little. But early in my research, I learned that no plant really likes low-light environments, but some plants just tolerate it. Empathizing, I started to give my aroids as much light as I could.

I also read about soil acidity and learned that many of my favorite flowers—including hydrangeas, foxgloves, and azaleas—prefer highly acidic soil. The pH level, when balanced, can leave the plants brighter, hardier, and more vigorous. Hydrangeas, for example, look pathetically tired without their “glass of lemonade,” as I began to picture the acidity.

As an apartment-dweller, I thought perennials would be off-limits. But many urban gardeners online mentioned that they enjoy perennials during the growing season and then place the bulbs in a shoebox or a paper bag in a dry place inside. So now, my closet is filled with shoeboxes full of daffodil and crocus bulbs, waiting to be buried somewhere next year.

All that said, the most shocking self-realization was that overall, flowers did little to impress me. I enjoyed them, but more in a casual way. My unexpected favorite thing to learn about was vegetables. There was one photograph on Reddit that really did me over, a picture of freshly harvested carrots. The carrots were all deformed, with multiple legs and limbs going every which way. They looked nothing like the pointed Bugs Bunny carrot—they were funny. Someone commented on the photo and said a good trick for next time would be to mix sand in the soil, to help the carrots grow further down in a straight line. The whole thing was odd, and I was in love.

The soil in the sand comment began to demystify something that always seemed so complicated—growing my own food. Over time, I realized that growing food is both practical and nuanced. Modern capitalism and norms like fast food have tricked society into thinking that farm-fresh food is some kind of delicacy. But when you pull the curtain back, you realize it’s a practice that is reasonably simple and really human, but that most people are deprived access to it. It’s practical because, for example—as I learned in Better Homes and Gardens—you can cut up a tomato and bury the slices to grow tomato plants. But it’s nuanced because the ways in which people plant tomatoes vary across geographies, cultures, and old wives’ tales. In Florence, for instance, tomatoes were mostly used as a tabletop decoration until the end of the 17th century—so growing practices were focused on aesthetics. In India, however, when tomatoes were first brought by Portuguese traders in the mid 16th century, the ingredient immediately introduced a new depth of flavor to Indian cuisine.

A great embodiment of this rich collective of food-growing knowledge is the Farmers’ Almanac, which has been around since the early 19th century. The periodical is released in August, near the end of summer every year, and predicts the next two years of weather patterns. And with those weather patterns, in conglomeration with the moon cycle and various folklore, it tells you when you should stay in, when you can go outside and plant, and even when you can participate in certain sporting events.

Scientists have studied the claims of the periodical and found them to be approximately 50% true, so no more or less true than random chance. In any case, I was intrigued by its lore. I immersed myself in it, spending hours at the library learning about the moon and its mythos. The editorial history of the almanac is full of gardeners, philosophers, scientists, and poets. I felt l like I was a part of something, in awe of how this strange magazine could predict life two years into the future.

In it, I came across a great article, “How Much Daylight Are We Really Saving?” exploring the very question I began with. Why are our days being stolen from us? It’s a vexed point of debate, and the article presents multiple arguments both for and against daylight savings. Many believe that later sunsets cause more activity out of the house and on the roads, wasting energy and perpetuating pollution. Conversely, others are concerned about safety and efficiency, wondering if sunlight is better utilized by the majority of people in the morning or in the evening. But rather than doing away with daylight savings entirely, the Farmers’ Almanac proposes a revised solution, which is to better schedule when it occurs.

The idea is rooted in civil twilight, which astronomers define as the 30-ish-minute span of time before and after sunrise and sunset, in which the sun is technically gone but that there is still enough light outside for humans to continue operating. Thinking back to my halftime show at the football game, that period of crushing sadness I felt occurred during civil twilight.

The proposed adjustment would make it so that civil twilight occurred around 6 a.m. and 6 p.m., making the official time change happen in early April and early September. With that adjustment, humans could slowly ease into the darkness of winter over a month or so. As it is now, fall back occurs in late October or early November, which throws us into winter light over a quick and traumatizing weekend.

Thinking about how to best optimize daylight made me want to learn how to best optimize my favorite season—summer. So in February, I decided my dim back porch would not suffice. I would continue to plant shade flowers there, where they had thrived in the past, but I needed something more. After devouring all this literature and learning, I decided to plan a vegetable garden.

There is a community garden near my apartment in Albany Park, not far from the Chicago River with plots you can rent from April to October. I calculated that this timespan would allow me to harvest in late spring, summer, and early fall.

I read about how to structure the garden. I learned about French intensive gardening—which is meant to optimize and rotate your harvests by season—as well as square foot gardening—where essentially every plant gets a square foot of space to grow. For the first year, square foot gardening would do. I also studied companion gardening—a growing philosophy that’s decently-backed—about how certain plants do well near one another and others don’t.

For instance, cucumber vines give good shade to cool crops such as lettuce and spinach, but shade out hot crops like peppers. Root veggies such as radishes, carrots, and beets don’t like being too close together because they are wont to hog nutrients. Onions can’t grow near beans because they exude a substance that is poisonous to bean roots. Then, there is planting that encourages natural insect management. Sunflowers draw healthy pollinators to the plot, whereas “trap crops” like marigolds are beautiful but stinky flowers that keep slugs away.

On the day of the garden registration, I woke up early and eagerly put down my deposit. At around $80 for over six months of growth, it felt like a reasonable deal. Then, I began counting.

I counted down the days until the garden gates would open. I took my son for wintry walks by the river, where I could only imagine the greenery that would take over in summer. One day, we visited the community garden that we would soon be a part of but it felt like a fantasy. At the time, it was little more than a dead pile.

I surfed gardening hashtags in the glow of my phone well past midnight, knowing I would be up at 5 a.m. pouring Cheerios and milk. I studied temperatures and zones and ritualistic methods such as planting seedlings on overcast days—the theory being that direct sun could traumatize the plant on its first day out, dropping eggs into the soil—the idea there being the protein and bacteria could strengthen the veggies, and pruning in dry weather—to prevent the spread of disease.

The more I studied, the more I began to resent the term “green thumb.” I used to love when people told me I had a green thumb, but someone with a green thumb is just someone who actively cares for their plants. Likewise, people who say things like, “I can’t keep anything alive” really just don’t care to.

I grew increasingly preoccupied, which both remedied my depression and exacerbated it. Sometimes I felt focused, inspired. Other times, I felt like my studies were a desperate escape. And though my research was mostly scientific, in the bleak winter, much of gardening felt like a fairy tale.

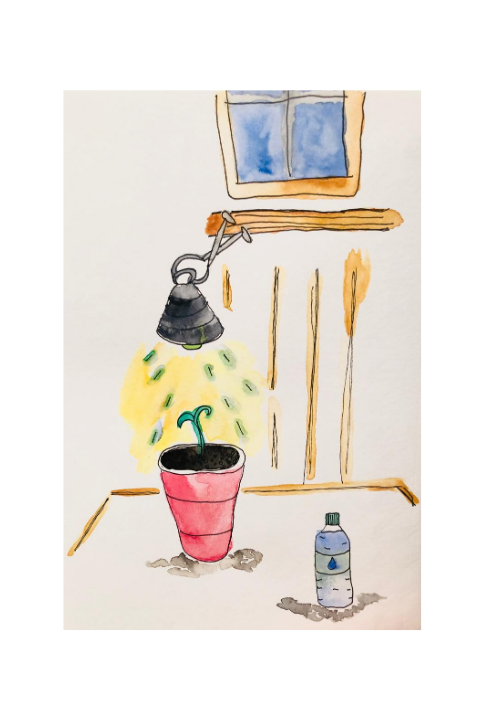

I needed the real thing. So in late February, I went to the hardware store and purchased a stack of red solo cups, two bagfuls of starter soil, three clamp lamps, and three green grow bulbs—the cheapest there was. There is a lot of criticism about vegetable gardening, how it is lauded as something that can save families money but actually is commodified like everything fucking else. It can get expensive—non-GMO, organic, heirloom seeds are marked up, stakes and fencing and fertilizers are outrageous, grow bulbs are ridiculous, and even tiny seed starter pods can add up.

I went the cheapest route possible, demanding that Andy, who works as a caterer, bring home reusable takeout boxes to hold my soil. A big part of my winter growing experience was actually saving trash—styrofoam beans and rice containers from Popeyes, Yoplait cups with holes punched in the bottom, stacks of cardboard egg cartons.

After all my effort, my makeshift greenhouse was a sad sight—a pile of recyclables positioned beneath some grow lamps on my windowsill. The structure was like an offensive mockery of the sun. But as ramshackle as it looked, it was the most earnest thing I had made in months, and looking at it filled me with love.

For better and worse, my love fed the plants. They grew with surprising violence. In a matter of weeks, the friendly heads of seedlings that poked up from the soil became intimidating monstrosities. The tomatoes grew gangly and pointy, with thick white fur lining the stems. The cucumbers began to twist around themselves and their neighbors, strangling pepper plants nearby.

You see, when I planted the seeds, I did not expect them to grow. As a sad person, maybe, I didn’t think I deserved that—and I also didn’t yet understand that plants want to live, and will do anything to live. Because I did not expect them to grow, I did not have anywhere in my 1,000 square foot apartment for two dozen fully-grown vegetable plants to take over.

And then, the coronavirus was everywhere, and a stay-at-home order was put in place.

We were trapped in a two-bedroom jungle—my energetic child, my neurotic dog, my panicking husband, and me. The air in the home began to smell of musk and mint, scents that did not pair well together. Augie began to refer to the plants as “the babies” and wanted to help water. Andy trailed behind us with a mop and a dishrag. Everything was wet and muddy.

I spent the days obsessively transferring the plants from their solo cups to larger cups. Their roots were outdoing me. I couldn’t bear the thought of losing even one, so I spent hours rotating them below the lamps.

Spilling and sweeping, spraying and draining. There was a period where I brought them into the bathroom for every shower. They sat on the outside of the bath, inhaling the humidity. When I got out of the shower, I would crouch beside them and touch every stem, making sure they were okay.

I could feel myself driving Andy crazy. I could feel myself driving myself crazy. I had this fantastical end-goal of becoming a homesteader—a joyful, do-it-yourself urban pioneer. I would stand on the lawn every morning with a hose, waving at the neighbors and nurturing my vegetables from farm to table.

In the quarantine doldrums, it occupied my every thought. When I sat down to doodle, my illustrations were only of vegetables. The books I read were only about permaculture. And the concept of permaculture itself riveted me because the whole basic idea is to replicate nature with your own designs. So the clamp lights, the forced humidity, the mud—it was all my own little permaculture design, as hideous as it was. In spite of it all, I felt proud of my garden.

My garden.

I never thought I had a garden—garden, garden, one of my favorite words. It evokes so much in me. I once read a definition of “garden” that called it a planned space. The definition made me realize that the mess of agriculture in my house was, in fact, a garden. It didn’t just happen to me. I had authority over it, and it was mine.

During the height of quarantine, there was a lot of new literature about gardening and mental health. Most of it was geared toward wealthy people who live in the suburbs. I lustfully scrolled through photographs of upper-class individuals transforming their driveways into container gardens, abandoned side-yards into ponds. From the Washington Post:

If someone were to say I must self-isolate in the garden for the next few weeks, I would shake him or her by the hand. If I could. Here’s a

thumbs up from a distance of six feet or more. The neighborhood sidewalks and nature trails are thronged with the cabin-fevered, so what

better place to be outdoors and yet away from others than in your backyard and garden?

He was talking about me. I was either holed up in my miniature condo or I was one of those people thronging his sidewalks. I stared up over my screen into the greenhouse my apartment had become. My garden didn’t give me the spiritual wholeness this columnist, and so many others, referenced, but it gave me a satisfying sense of safety and beauty and most of all, control.

In late April of 2020, the community garden opened on a cold day. The tenant from the year before left my plot a disaster. I worked in it until after dark, digging without gloves, my cold hands scraped and ripped by abandoned chicken wire, trellis fences, loose hard vines, and winter rock.

For hours, I ripped that tiny lot apart. I cried in frustration at my aching hands and the plague-ridden world and the rich people and the people who refused to wear masks. I cried about Chicago, that it was so cold and annoying. I cried for no reason, really, other than that it was my first time to really leave the house in weeks. And it was my first time to be alone in what felt like ages. And just because I wanted to.

At the end of the night, I stepped back with a tiny flashlight and looked at what I had done. There was a perfect plot of soil waiting for my plants.

From then on, everything continued to be imperfect. A mid-May frost murdered three of my tomatoes and all of my peppers. Some urban creature ate my basil and my cucumber. My radishes harvested perfectly, but with tiny slug bites taken out. But with every misstep, I took a note and tried again.

Sometimes when I am working there in the evening and the sun starts to set I feel the dread I felt in 2007 and always, when I get so sad the days end because I don’t feel like I am taking advantage of them. I have this weird habit of looking at my fingers and counting down the months until November when I will have to say goodbye to the garden. I am afraid I won’t do everything I want to before then. I am afraid of not growing all the vegetables I hoped for, or worst of all, killing them. I am scared about next winter when I will be counting down again until spring. I am scared about the coronavirus growing and growing while we all drive ourselves batshit in our desperate hunts for joy.

Last week, Andy and Augie and I ate fresh beets on crostinis and bowls full of kale. I run to my plot excitedly every day, so I can spy on the tomatoes and the peppers and the cucumbers as they slowly say hello.

The summer solstice is over, the days are growing shorter, but it isn’t over yet.

Caroline Macon Fleischer is a multi-genre writer, editor, and theatremaker. She lives in Chicago with her husband, son, and Border Collie.